Throughout our long and winding history, there has been nomads and settlers. There have been hobos and explorers, freaks, and beatniks, and wayward vagabonds. So where along the way did the backpacker as we know them today come from?

Did they spawn, fully-fledged and dreadlocked, from the soupy backwaters of Thailand? Did the red light district of Amsterdam release a hash seeking spirit that infects the young and unemployed?

Well, probably not. As with the best history though, the truth is far stranger than fiction. The history of backpacking has long tendrils that connect the nomads, the hobos, the explorers, and the hippies. As I delved deeper into this question, I found myself slightly obsessed.

The Hippy Trail and all its kombi van and Kandahar hash glory lights up the timeline and still inspires many a loose and wayward traveller today. But is that the whole story of the origins of the backpacker? Not even close.

And like any good history, I started to wonder: if this is where backpacking came from, I wonder where it is going…

So, I present to you: an abridged history of backpacking, in which you can read my descent into insanity and back to clear-headedness. Light up a joint, prepare to pack up your bags, and stick out your thumb. We’ve got some learning to do.

Photo: @_as_earth

What IS a Backpacker?

First things first, what kind of backpacker are we hunting the origins of?

When I say backpacker, you might think mid-twenties, long hair, penchant for the good hashish, probably wearing tie-dye, definitely a little smelly, and their worldly possessions fit into their eponymous backpack.

But if you ask some folks, especially in the USA or Canada, they’ll tell you that backpacking involves carrying your food and shelter on your back as you embark on hikes across the world.

This kind of backpacking and the return to nature, or pursuit of solitude, began in the 1920s. It really rose in popularity in the 1970s with the invention of the internal frame backpack and with the mystique of a certain other type of backpacking.

Photo: Gerd Eichmann (WikiCommons)

This certain other type of backpacking is the one you probably first thought of.

This kind of backpacking is the low-cost vagrancy; the scrappy race to the bottom of the doobie; the Bohm Shiva delight that we all know and love. This kind of backpacking has a stench of authenticity.

It’s an education, or personal development quest, more than it is tourism. It’s about writing your own manifesto and slowing down.

As we’ll see, from its hazy origins, backpacking has been about trying on another way of life and reconfiguring your own perspective. The best kind of backpacking is about travelling slowly, engaging with the locals, and taking nothing for granted.

Photo: manhhai (Flickr)

More than any of this, backpacking has always been a story. And it’s this story and mythology of adventure that remains so enduring.

There’s an element of escapism rife in both types of backpacking. Mainstream society is too industrialised, too square, too regimented. And so we seek the solitude of the bush or the teachings of the open road. Escapism and freedom are good excuses to get high and backpack through Iran to India.

Plus, what a freaking story!

But the yearning for meaning that has backpackers hanging on for dear life to the rooftop of buses and learning to ride a camel across the Rajasthani desert… Is that meaning truly found in escaping society?

Besides, when did backpacking begin? And why are weed and a lack of deodorant two unshakable stereotypes of the wild-eyed backpacker? Alas, we are only at the beginning of our quest for answers; we must dive deeper into the rabbit hole.

Unlock Our GREATEST Travel Secrets!

Sign up for our newsletter and get the best travel tips delivered right to your inbox.

Where Did Backpackers Come From?

If you follow any timeline back far enough, you get to the Big Bang. And then, depending on who you ask, God or nothingness – or maybe they’re the same thing.

Anyway, I’ve yet to find any evidence that backpackers tumbled out along with the original bits of space gunk and star explosions, so I’ll leave the galaxy behind for now. Closer to home, temporally speaking, which of our ancestors first went walking and seeking solitude outside the tribe? Who had to hit the road and find themselves while intoxicated on the stunning beach of a faraway land?

Nomadism

Just over 5000 years ago, Otzi died and he and his backpack were frozen in the snow of the European Alps. This is one of the oldest pieces of evidence that we have for a backpack and a person on a journey together.

But we know that until 10,000 years ago (give or take) it was humanity’s norm to wander. Even as we did settle down and begin to farm, our quality of life usually deteriorated! We had greater diversity in our diets and more leisure time when we were nomadic. So I take it that some part of my DNA is still whispering to me about foraging in the morning and then chilling by a lake all day.

We don’t think of backpackers as nomads though. We might appropriate words like ‘digital nomad’ and we might claim to have no home, but a backpacker has a choice. A nomad who migrates depending on the seasons and lives completely off the land doesn’t have a settled base that they’re avoiding paying taxes in. 😉

A medieval farmer’s kid who decides to take off and try out a new way of living in a far off and distant land has more in common with the modern backpacker than a traditional nomad does.

Because backpacking has always been about seeking escape from something stale and sedentary.

Yet, I think it’s important to acknowledge that for most of our history we had no fixed address. There was no one place that you were from. And when I’m out hiking, I do feel an echo of something ancient within me tell me to simply keep moving. I think every backpacker who embarks on a journey has a similar feeling: that to move on is to return to something long forgotten.

We call this wanderlust and seek to escape home; perhaps we should think of it more as returning home.

Age of Exploration

Agricultural revolutions and the complex arches of our early history aside, I think the next step toward the modern backpacker was the Age of Exploration. Or at least, the narrative that surrounds this era.

This was a time of Europeans setting sail to lands unknown to them, determined to make money, spread the word of God, but also to ‘discover’ what was in each corner of the globe.

Almost all the lands Europeans stumbled across were beyond their wildest imaginations – and filled with Indigenous people. Here is perhaps not the forum for me to air the proximate and ultimate causes of colonisation – or my very ‘fuck-the-imperial-powers’ opinions on colonisation’s consequences. But there are still important, and perhaps uncomfortable, pushes forward toward the modern backpacker that occurred during this time.

In large part, the Europeans that set sail were looking for gold, silver, and spices, as well as new trade routes. Increasingly, there was also a push to fill in the gaps on the map, explore new territory for the sake of exploring it, and to missionise those they encountered. What does this have to do with backpacking?

I think that the stories that the explorers brought back have infected our imaginations to this day. Stories of paradisiacal islands (like Fiji), of sea monsters, of storms, of the intrepid adventurer rising over insurmountable odds were brought back and continue to inspire modern travellers.

To me, there are parallels between the race to fill in the map and the race to fill one’s passport. Both the explorers of this age and the modern backpacker are eager to escape a stale life at home for an adventure abroad; yet, almost paradoxically, they seek to make the world smaller and more accessible. They want to prove that what’s over there isn’t something to be feared, but something to be embraced.

The Age of Exploration has a complicated legacy. But in making the world more connected and by infusing our imaginations with tales of adventure, these explorers laid the seeds for the modern spirit of backpacking. The historical accident of Europeans exploring and colonising meant that it was the Europeans who became the majority of the modern explorers too.

There’s perhaps a little poetic irony in that now we are not footsoldiers of Christianity but capitalism. Where there was once a missionary bringing the word of God. Now there is an offer to employ local staff in a backpacker’s latest adventure tour, harbouring the good word of the Almighty Dollar.

This highlights the need to look at the attitudes that we bring to a country. You don’t want to be extracting experiences, littering, or pushing your worldview at the cost of the locals any more than you want to be a bloodthirsty conquistador. You want to practise responsible travel.

The OG Hobos

There is something more to the imagination of a traveller than simply exploring lands unknown to them. There is something gritty that pushes them to work on the road and earn their doobie. Now, where did that come from?

I’d say that the American hobo culture is the twin cultural pole of modern vagrancy. If the European age of exploration and its dashing romanticism and potential for unintentional ill consequences on local populations is one end, the hobo code is the other.

I don’t strictly want to compare most backpackers with hobos. Hobos are their own cultural group with a history stretching back to the early 1800s – particularly along the railway lines in the USA. But insofar that:

- Hobos find work while they travel

- Tramps simply travel

- And bums don’t travel nor work…

The backpacker culture has taken inspiration from hobo culture.

The train-hopping, dumpster diving, hitchhiking, no fixed address, permanent itinerancy that a few backpackers strive for comes from the hobos. The eternal hobo conversation starter, why did you leave home, is one that resonates with a lot of us.

There’s a loose code of ethics that focuses on doing no harm and finding odd jobs. And there’s a big love for music and storytelling.

The hobos are distinct from backpackers; most backpackers eventually find a home. A hobo’s home will always be the road (or the freight trains). But the practical adventure grit that inspires many long distances travellers can thank the hobos for their origins.

Camp stoves and campfire culture; pseudonyms and origin stories; working to pay your way to the next destination are all staples of backpacker and hobo culture.

I think it’s interesting that the American backpackers I meet are far more inspired by solo thru-hikers and hobos; whereas the European backpackers I meet are more concerned with crafting themselves a narrative of exploration.

Either way, most of us drifters and grifters can unite over a cheeky joint at the end of the night!

The (in)Famous Hippy Trail

What do you get when you mix the adventurous stories of old European explorers with the itinerant hobo culture of finding jobs along the way? Introduce the mix to the counterculture of a Cold War society… There you have a wanderlust generation.

The wanderlust generation were the children of World War II veterans. They were the first generation of recreational drugs and counter culture. As the 1960s kicked into gear, the world was a-changin’.

The squares looked in at them and called them ‘beatniks’ and then ‘hippies’. The hippies looked out at the world and declared themselves ‘freaks’. Either way, the old system wasn’t for them and the new system would be ushered in after this joint. There were plenty of poets and wanderers inspired by the hobos that took to the road a la Jack Kerouac.

Photo: Gerd Eichmann (WikiCommons)

But more importantly, there was a disenchanted feeling with the Western Order: capitalism, consumerism, and Christianity were all morally and spiritually bankrupt. Consequently, many that wandered the hippy trail went searching for other ways of thinking. Mysticism (which tends to go hand in hand with hash, but that’s another story) was on the rise.

One thing that comes up again and again when talking with old school freaks who wandered the hippy trail is the breathless excitement of dawn in a new country. You would leave a scribble in a coffee shop while backpacking Istanbul, promising to meet a lost love on the beaches of Goa. But you never really knew where the wind would blow you.

And to trickle into Istanbul as the sky rang in a mauve chorus for sunrise, you really felt like you were discovering the world. Things like border crossings were a matter of negotiation (Iran was always a little tricky) and at each stop along the way, you simply had to find a notice board full of tips left by other travellers.

The Hippy Trail was solidified as a bona fide counterculture must-do when the Beatles went travelling in India. But when the Beatles floated by in 1968, they went to towns already known along the Hippy Trail like Rishikesh, India.

They were in town to learn transcendental mediation and cure the spiritual exhaustion that came with fame. After staying at the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, they denounced drugs in favour of meditation. My own grandfather took to the Hippy Trail and spent time learning to write Iranian ghazals and finding his own Guru – Meher Baba – in Pondecherry, India.

This seeking of spiritual knowledge outside of the West was a big part of the original backpacking scene. To become a backpacker was an act of defiance, almost protest, at a time of upheaval. I think the biggest force on the origin of the modern backpacker was to seek a life – and by extension, a spirituality – foreign to the one you grew up knowing.

Big ideas aside, there was also a lack of affordable long haul flights and open, easily accessible land borders. This was a glorious combination for the young, unemployed, and disaffected. You could get on a bus from London or Amsterdam and end up in Tehran for next to nothing.

So yes, the dreamers were going to change the world. They were going to fall in love with the loveable chaos of Kathmandu and unite Eastern and Western values. They were going to take a stand. But they wouldn’t have been able to do that with closed borders or more expensive overland transport.

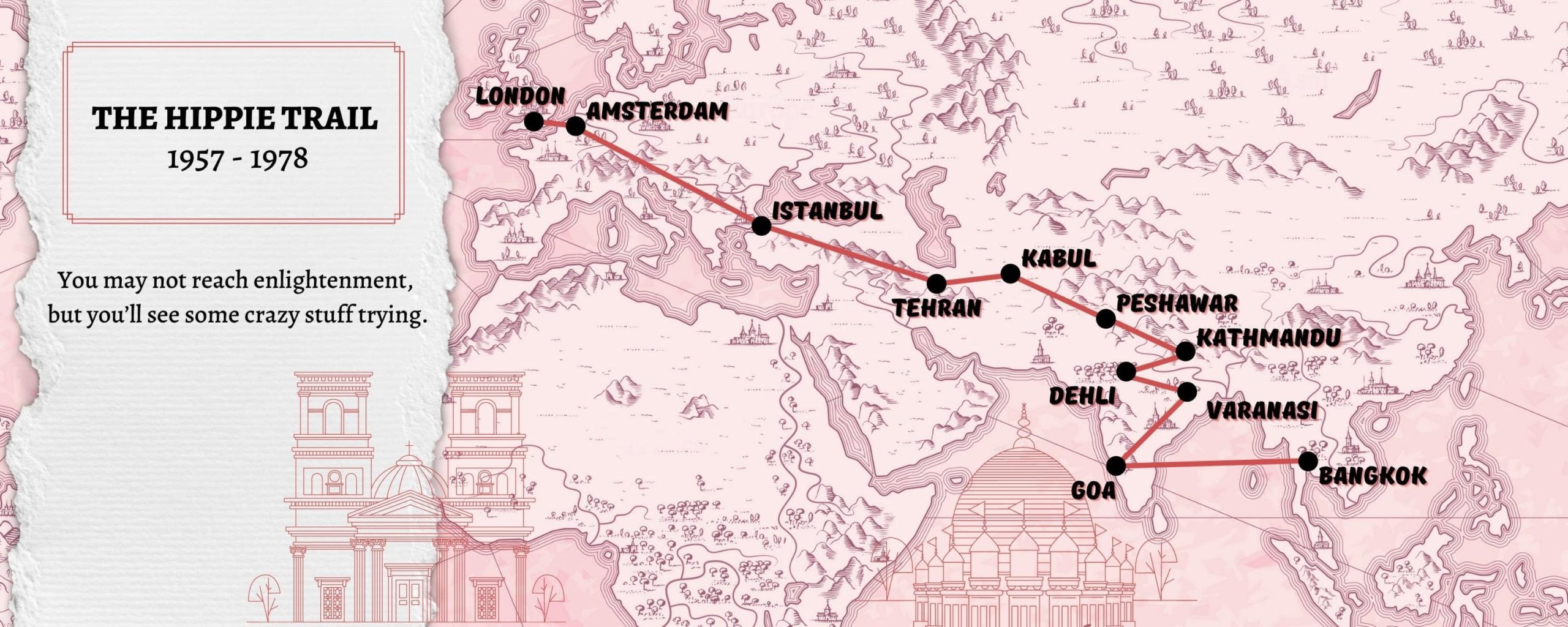

Routes of the Hippy Trail

I think the counterculture rejection of deodorant and penchant for hashish has remained a stereotype of backpackers to this day – and with good reason! But where were all these smelly hippies off to?

From Europe to Australia, that was the goal! But there were key stops along the way.

Backpacking Afghanistan was a key part of this hippy trail – especially since the hash from Kandahar was renowned for its quality.

Further west, Peshawar, Kathmandu, and then south to Goa were all popular stops. Many travellers went onto the then unspoiled beaches of Thailand and even further south to Australia.

How Did You Travel the Trail?

As cheaply as possible! You hitchhiked, caught local buses, trains, and ferries all the way from Turkey to Australia. You might’ve even had one of those clapped out kombi vans and lived the OG van life…

At each stop along the way, you tuned into the network of travellers that had come before you by checking the notice board for tips left behind by other hippies. Perhaps you carried a Lonely Planet book that carried hints about where to stay once you got to town.

Photo: Gerd Eichmann (WikiCommons)

All of your possessions fit into your backpack and you were living a life of freedom on the road, baby! Much more than other tourists, you were interested in the local people and culture. The Western culture was spiritually bankrupt, so perhaps a guru in India might cure your existential dread.

The open road called you and you stretched your money as thinly as possible to avoid going home. The only time you might splurge is on that Kandahar hash. 😉

My missus travels with all her clothes in ziplock bags: don’t be like my missus. UP YOUR PACKING GAME!

Packing cubes for the globetrotters and compression sacks for the real adventurers – these babies are a traveller’s best kept secret. They organise yo’ packing and minimise its volume too so you can pack MORE.

Or, y’know… you can stick to ziplock bags.

View Our Fave Cubes Or Check Out the Sacks!Where Did the Trail Go? A Perfect Storm

We have a whole new generation of backpackers today, but they’re not taking to the Hippy Trail. Really, the Hippy Trail lasted from the late-1950s to the mid-1970s. What happened to it?

A decade after the summer of love, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and the Iranian revolution occurred. Both countries went from places that were popular stops along the Hippy Trail to an active war zone and a place hostile to Westerners, respectively.

At the same time, the price of airline tickets was becoming more affordable, so it wasn’t strictly necessary to only travel overland in order to be a budget traveller. Slowly, backpacking trips became confined to regions such as the Banana Pancake Trail in Southeast Asia or the Gringo Trail through Latin America.

Fun fact: The Banana Pancake trail was coined as the guesthouses of Southeast Asia. They realised that one thing these strange, long-haired foreigners loved was banana pancakes.

But you can’t entirely blame the wars for the demise of the Hippy Trail. The hippies and freaks could’ve taken to the Silk Road, or found bohemian paths across other countries and continents that weren’t at war.

And then there is the argument that the inadvertent carelessness of the backpackers helped spur on the cultural shifts that lead to both the Soviet Invasion and the Iranian Revolution… Oy vey, the ghosts of the European explorers had one last accidentally-fucked-this-country-up hurrah.

Photo: manhhai (Flickr)

Ok, you can’t lay the upheaval of an entire region at the feet of these smelly hippies. But other than the increasingly affordable flight, I think there was a cultural shift that contributed to the demise of the Hippy Trail.

The height of the hippie movement was arguably 1969 and had truly fallen away after the Vietnam War was lost. With no war to oppose, the movement lost its unifying ideals. Because underneath opposing war, what does it mean to believe in freedom, peace, and love?

The pursuit of freedom (and cheap hash with a dash of mysticism) is an inherently negative concept. As in, it doesn’t stand for anything, merely in opposition to the old system. Sure, you get to reject the materialism of your parents but now what?

Degeneracy is fun but it’s hard to keep up as a lifetime occupation, as Pirsig would say.

As the decades stacked on top of each other and the neoliberal order was ushered in (ironically by the same generation that believed in peace and love) the days of uniting the world by backpacking the Hippy Trail seemed more and more distant.

I think as the USA ‘won’ the cold war, or was at least the last man standing, there was a sense that this is it. There was no need to go and experiment with mysticism or communism. Here in the West, democracy allowed you to freely try on other lives and then go on and try cheap wine in ex-communist Europe for pennies.

As the parts of the region remained unstable and a little nihilism crept in, the Hippy Trail slowly became relegated to the dustbin of history.

9/11 and the Internet: Backpacking in the early 2000s

Enough time has passed that 9/11 has started to feel like a strange and hazy nightmare. A surreal relic of failed geopolitics or a grand conspiracy, or just another thing that happened.

But fresh after the kapootzing of the towers, something shifted in the world. Airports became venerable ports of racial profiling in the name of national security. There was once again something to prove in going travelling.

You had to know that the world wasn’t as dangerous as you’d been told; there was something else to travelling other than a week in Cancun during which you never left the hotel.

You looked back to the time of the Hippy Trail and tried to recreate it in spirit with offbeat travel. These travellers were ready to connect with those that the media had painted as cutthroat terrorists. These values of bringing the world together through travel once again seemed possible.

The internet wasn’t the cesspit of self-propagating trolls and polarised Infowars yet and it seemed like it could aid in the backpacker quest to unit the world through travel.

Platforms like Couchsurfing, BeWelcome, and Workaway sprung up as a way to connect locals and travel bums. The internet democratised information – including backpacking information. The first travel blogs sprung up sharing tips and tricks – a little like this one here!

Accessible travel information and accessible flights meant that travel once again started to take off with purpose. There were still the tourists flitting in and out of resorts, but this generation of backpackers was finally going to do some good. We’d think twice about quitting our jobs to travel because it meant leaving for longer.

We were going to travel responsibly, give back to local communities, and prove to the world once and for all that we’re all human. We share one planet and it’s up to us to leave it a little better.

Is that the way backpacking and travel are going, though? Are we doing everything we can to ensure the industry doesn’t strip mine local cultures to serve the ‘enlightenment’ of a few privileged tourists?

A Brief Word on the Fearsome, Loathsome Drogas

Now, the history of recreational drug use of travellers is worthy of a 400-page book – which I’m more than happy to write one day. But I think it’s interesting that in the 1960s and during the heydey of the Hippy Trail, LSD was fast becoming the recreational drug of choice. While everyone’s always loved smoking marijuana, cheap opium and even heroin lured many hippies in as well, LSD defined the recreational drug scene of the 1960s.

As the Hippy Trail fell apart and even budget travel became confined to small spurts along fairly well-commercialised trails (e.g. South America or Southeast Asia), the recreational drug of choice changed too. Cocaine had its peak in the 1980s with 500 – 800 tons of cocaine per year entering the USA by the early 1990s.

And with the 90s, while a lot of people still smoked dope and LSD started to make a comeback, heroin got its gritty little paws around the generation.

I think it’s interesting that as the world became more accessible in terms of cheap airfares, and travel became more accessible, something “spiritual” was lost. This coincided, or perhaps was fuelled by, a cultural nihilism that was pervasive in the 1990s.

History was over. The West had “won” the Cold War. And yet, the West was driven by values that were as vacuous as ever. Cultural nihilism and heroin go hand in hand it seems.

And today? A buffet of the mind-altering good stuff is available to those that want it. It’s all still bound behind penalising and criminalising laws despite the growing evidence in support of harm reduction policies like decriminalising.

I think that the chaos of our politics and divided culture is reflected back in the soiree of drugs that are consumed.

Drink water from ANYWHERE. The Grayl Geopress is the market’s leading filtered water bottle protecting your tum from all the waterborne nasties. PLUS, you save money and the environment!

Single-use plastic bottles are a MASSIVE threat to marine life. Be a part of the solution and travel with a filter water bottle.

We’ve tested the Geopress rigorously from the icy heights of Pakistan to the tropical jungles of Cuba, and the results are in: it WORKS. Buy a Geopress: it’s the last water bottle you’ll ever buy.

Buy a Geopress! Read the ReviewThe Legacy and Consequences of the OG Backpackers

So where do we go from here?

There are many of us who still embark on a backpacking journey and completely reconfigure our perspective on the world. We want to see what a country is like up close. We want to be part of a better, more open world. And we still carry the drug-taking, love and sex having torch high, with pride.

But the double-edged sword of a more open world is that we can end up inadvertently supporting the very things we profess to want to change about the world. We love the Himilayas so much, and yet there are mounds of garbage on Mount Everest.

The convenience of cheap flights is shadowed by their enormous carbon footprint. The flooding of special places erases the local culture.

And besides, the drugs and freedom of backpacking are great, but they only take you so far in your quest for meaning. Even the adrenaline of a good adventure holiday wears off eventually.

Backpacking has stopped being a once-in-a-lifetime adventure that taught you about the world; it’s started to become something you have to do in order to be a well-rounded person. Not only that, but it’s a more fragmented world to travel than ever before. The dreams of porous borders and loving, multicultural havens on Earth seem to be growing more distant.

So if part of us is condemned to seek an itinerant life, how do we balance the double-edged sword? How can we become more responsible travellers?

The Future of Backpacking

I think that the future of travel should be slow. Learning the art of slow travel allows us to get in touch with the reason we left home in the first place without putting the same amount of stress on the environment or the local cultures.

There are many ways to slow down and embed yourself in a country and culture.

- Commiting to overland journeys.

- Learning the local language.

- Couchsurfing, or staying in a local homestay.

- Giving back and volunteering.

I remember, after living in Guatemala for 6 months, I surprised myself with how sad I was to leave the country. As I said goodbye to my machete-wielding neighbour, sold my canoe, kissed many cheeks goodbye, I thought man, it’s like leaving home all over again.

This country had been a place where I fell in love, learned to make tortillas, sat at the local tienda, learned to speak Spanish, and where I had felt most at home in many years. The community taught me so much and for that I’m grateful.

Sure, there was a lot of terrible tequila and cheeky joints consumed there too, but all in moderation. I guess, ultimately, if your travels aren’t teaching you anything, you’re probably falling into a backpacker’s trap.

The future of backpacking will always push for adventure. It will always be about connection. I think we have just grown more mindful of the impact of our lofty imaginations and dream to travel the world. I think more of us than ever are committed to ethical budget backpacking – and that’s the way it’s got to be if we want there to be a world to keep exploring.

Get your cash stashed with this awesome Pacsafe money belt. It will keep your valuables safe no matter where you go.

It looks exactly like a normal belt except for a SECRET interior pocket perfectly designed to hide a wad of cash or a passport copy. Never get caught with your pants down again! (Unless you want to.)

Hide Yo’ Money!Final Thoughts on the History of Backpacking

I feel that the Ancient Greeks had a good way of looking at the past and the future. The past is stretched out in front of you, uncomfortably familiar; the future lurks behind your shoulder forever unknown.

We can see our ancestors and their nomadic ways stumbling out of East Africa and across the globe. The urge to move with the seasons indefinitely has been coded into each of us – though some of us feel that echo more strongly than others.

Our mythology has been storied with travellers and vagrants: Jesus himself wandered, the conquistadors ostensibly wanted to see new lands, the hobos traded a sedentary life for freedom and loneliness.

And we can see what the OG hippies wanted to do. We can see what they wanted to learn. We’re also aware of the legacy of their original travels.

They sought solitude and maximal pleasure – all at once. They, perhaps inadvertently, turned travel into a commodity for reluctant consumers.

Still, there remain those of us today, committed to finding a little peace on the open road.

These days though, it’s harder to find a place of solitude. There are phones and overcrowded cities galore. I suppose that’s all the more reason to carry on that nomadic streak; to push the envelope a little further.

So here we go, I think I’ll finish with a poetic ode to the continuation of wayward vagrants:

Empty your pockets. Empty your path. You have only what you can fit into your pack. You know that whatever you are chasing is balanced by what is chasing you.

Remember that the price to freedom is often loneliness, so don’t forget to hold hands and say I love you. But above all, if it is to be a short life, then let it be a beautiful one.

And for transparency’s sake, please know that some of the links in our content are affiliate links. That means that if you book your accommodation, buy your gear, or sort your insurance through our link, we earn a small commission (at no extra cost to you). That said, we only link to the gear we trust and never recommend services we don’t believe are up to scratch. Again, thank you!